August 7, 1958 was a pivotal date in the history of Britannia Beach. It was on that summer day that the highway connecting Horseshoe Bay to Squamish was completed. A company town’s half century of isolation had effectively ended. Hardly more than an hour’s drive, the miners and their families now had easy access to the big city.

In 1960, two years after the completion of the road, and thanks to the BC Mountaineering Club, a friend and I were introduced to the mountains above Britannia (as it is abbreviated). The Sky Pilot Range: overflowing with alpine splendor, with heather meadows and tarns, challenging spires and even two pocket glaciers. We were smitten! That same road that was luring the town’s folk to the city lights had made the Squamish area accessible to Vancouver weekend adventurers.

Throughout the year, including winter, and throughout our high school years my friends and I seized every opportunity to explore the Sky Pilot area. We hiked all the ridges and climbed every peak and pinnacle.

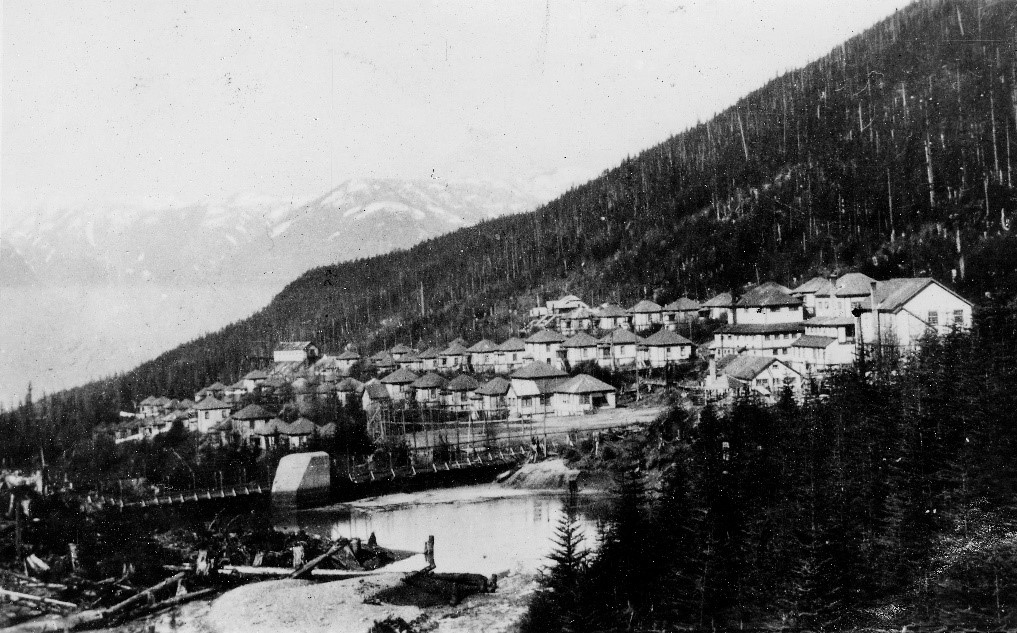

How did we high school students actually get to Britannia? Sometimes my friend would borrow his mother’s VW Beatle. Sometimes no car was available and we’d hitchhike. Once at Britannia, we would either drive or hike up the five km to Mount Sheer, also called the Townsite, which was where the miners and their families lived. (The mill workers and management lived at the “Beach,” the area beside the highway). In the early 1960’s Mount Sheer was still a lively little town with a hospital, a school, even a heated outdoor swimming pool. There were neat rows of company houses, children playing, laundry on the clothes lines: in effect, families going about their ordinary daily lives. It was something of a surprise for me to find a small town tucked away in the mountains and so close to Vancouver.

Four or five km beyond the Townsite, following a logging road and then a trail, was a simple but sturdy log shelter that had been built by the miners and which they had dubbed “Sky Pilot.”

Sky Pilot cabin became our base camp. Likely because of the aforementioned recently established road link to Vancouver, the miners now no longer, or at least very seldom, visited their alpine refuge. We virtually never encountered anyone there. We had the cabin to ourselves, as also we had to ourselves the crags and the meadows with their late summer bounty of blueberries.

Those dozens of trips in the early sixties into the wilderness area at the head of Britannia Creek left an indelible impression. Youthful adventure; the experience of nature in all its formidable and delicate beauty and its dangers; the forging of friendships: it was all there.

The Sea to Sky Gondola now offers relatively quick access to the peaks, and the Sky Pilot Suspension Bridge provides tantalizing mountain and fjord views.

Over the decades I have returned to this area many times. In early September 2001, I climbed Sky Pilot Mountain with my two youngest children. A few days later came the fateful 9/11 attack.

My painting of Sky Pilot Mountain that now hangs at Copper Ridge Conference Centre was inspired by two events. The first event: those pilots, inspired by a false zeal, crashing into the twin towers; the second event: reaching the summit of Sky Pilot Mountain with my two young children, an event both happy and exhilarating.

Often mountaineers will build a cairn on the summit to indicate a first ascent. There are also, of course, other kinds of cairns, for example, memorial cairns.

Sky Pilot has two summits. In my painting I have exaggerated the steeper one, which in reality is the lower of the two summits, for visual effect. In the background you can see Garibaldi Mountain.

A noticeable feature of the painting is the calligraphic circle shapes that act as a kind of veil. This indicates the first snowfall of the season. Prominently in the foreground is a cairn which is engulfed by the towering shape of the pinnacle. Both hint at a spiritual reality.

Most of the canvas was painted in acrylics. The dark central shape was painted in encaustic, which is pigment mixed with beeswax.

Most of the canvas was painted in acrylics. The dark central shape was painted in encaustic, which is pigment mixed with beeswax.